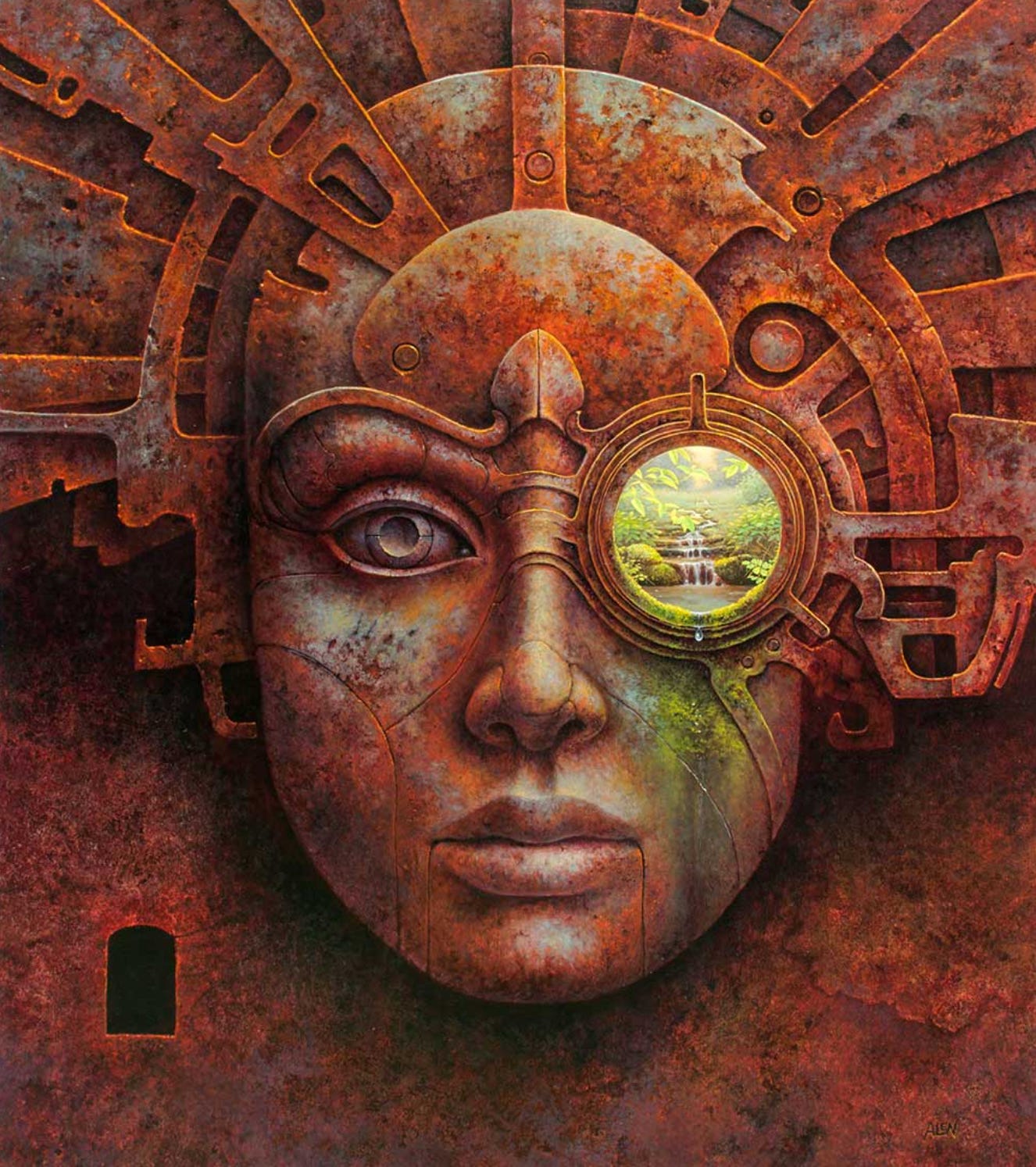

Until I was 28, I chased a life that was not my own. I was drunk on a cocktail of ambition, achievement, and accomplishment. The firewater could not quench my thirst. No matter how much I drank, I never even tasted it.

The cocktail was my “potential.” The possibility that I had great things to birth into the world. My towering contributions that would pr…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Deep Fix to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.