The block universe and the slice you’re in

Einstein, Interstellar, and the strange freedom of living in spacetime

In a famous letter to the widow of a family friend, Einstein once wrote:

“For those of us who believe in physics, the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

It might sound a little obtuse, even bypass-y to someone grieving. But it was probably just a genius’s best attempt at consolation, reminding her that her husband wasn’t gone because every moment of his life still existed in the fabric of spacetime. And it came straight out of his theory of relativity.

Once Einstein demonstrated that space and time are inseparably linked, the traditional picture of time as a single, unidirectional flow for everyone no longer held. Instead, it opened the door to a new view: that past, present, and future all coexist in a four-dimensional spacetime manifold.

Physicists call this the “block universe.”

Welcome to eternity

It’s sometimes nicknamed the “loaf of bread theory,” because physics is easier to swallow with carbs.

Picture it as a loaf of sourdough. Each slice is a moment in time.

You only ever taste one slice at a time, but the whole loaf—all of time and space—is already there.

In philosophy, this view is known as eternalism.

And you are something like the knife of consciousness:

Slicing into the loaf, tasting one moment after another, yet never escaping the fact that the entire loaf already exists.

Your Batman-themed birthday party as a seven-year-old is still there.

Your eightieth-fifth, god willing, is there too.

Because there’s only one universe that’s already perfectly complete.

No single universal present

If Einstein was the first to sketch this view, physicist Brian Greene has become one of its clearest modern explainers. He has a thought experiment designed to obliterate your sense of time:

Imagine an alien ten billion light-years away, holding up a clock and pointing to what they call “right now.”

Because light takes time to travel—and because relativity shows that motion itself warps our perception of time—their “present” would not line up with yours.

What they count as now could include events you would swear are centuries in the past or centuries in the future: your death, your great-grandchild’s wedding, even the extinction of humanity.

And this is where Greene adds nuance to the tidy loaf metaphor. The previous diagrams make it look like everyone shares one giant “now.” But relativity already proved that isn’t true.

What Greene adds is a way to visualize it. His thought experiment reveals that “now” itself is relative—different for every observer, shaped by where they are and how they’re moving. In other words:

There is no single universal present.

Which brings us back to the human scale. Instead of one master clock keeping time for the universe, there are only perspectives, each slicing the loaf in its own way. The present moment isn’t a fixed location so much as something to participate in, a way of seeing.

Not just for physicists

The block universe first became fascinating to me on a meditation retreat, of all places, when Dr. Shamil Chandaria, brought it up between sits. He studies consciousness at Oxford, Harvard, and Berkeley, so he thinks about these things. As we talked it over at lunch, the idea began to transcend physics, like something I could actually turn towards in practice.

Contemplatives like him—meditators, neuroscientists, Dharma junkies—form one camp deeply interested in the block universe, spending thousands of hours experientially discovering that past and future are nothing more than thoughts arising “now.”

The other camp is our culture at large, which continually retells the same intuition through stories and myths, especially in film.

Some of the most memorable movies of the past decade have been obsessed with time. Everything Everywhere All at Once, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 2023, captures in its psychoactive title alone the disorienting truth the block universe points toward:

That everything is happening everywhere, all at once.

The film plays it out in a frenzy of parallel lives and absurdist chaos. It’s not a block universe but a block multiverse, creating a trippy metaphor for what it feels like to imagine all of time existing simultaneously.

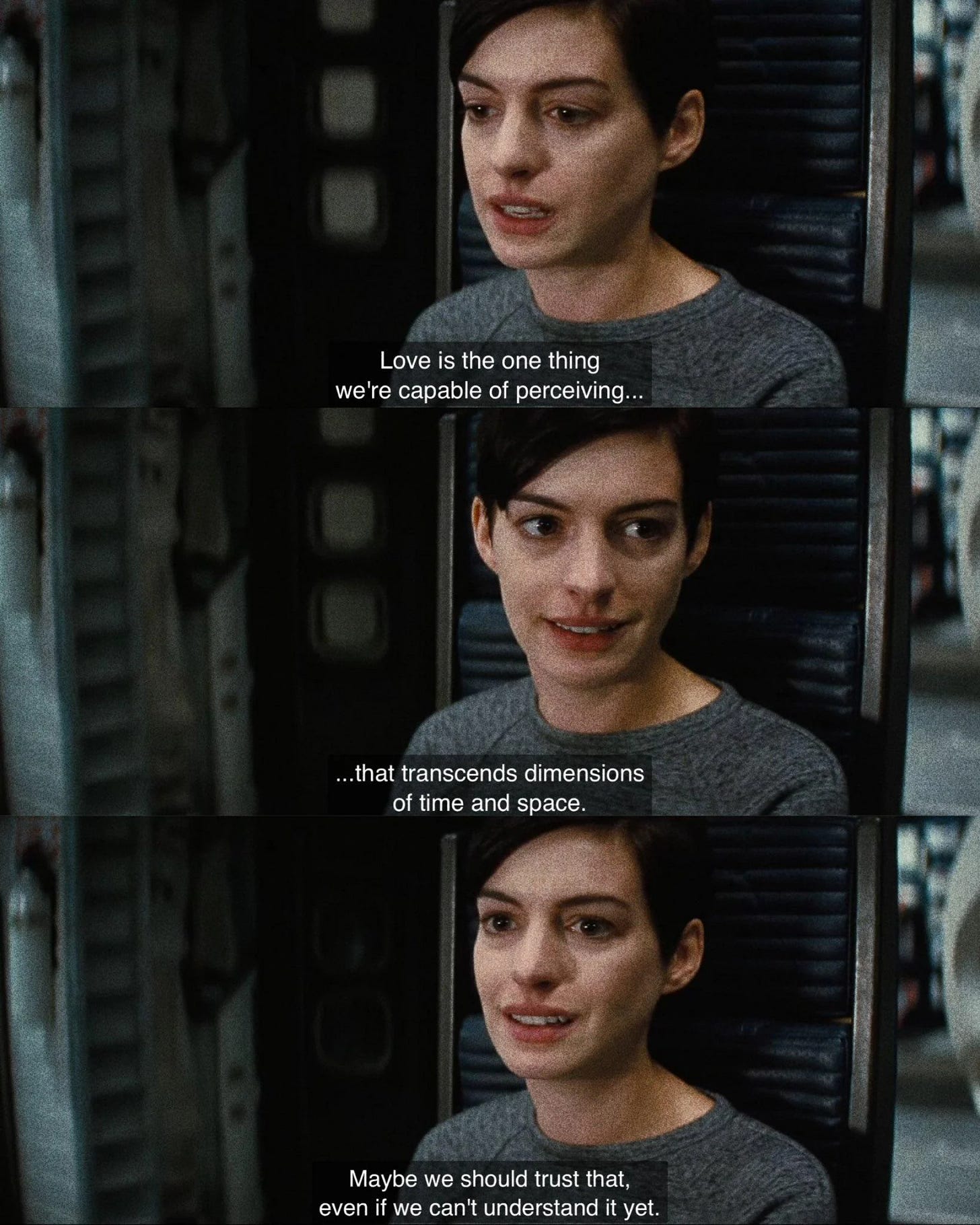

If EEAAO portrays this idea as manic comedy and heartbreak, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar renders it as something far more intimate (spoiler alerts below!).

The climactic bookshelf scene with Matthew McConaughey’s Cooper pounding on the walls of spacetime to reach his daughter comes closer to what physicists actually mean when they talk about the block universe: past, present, and future laid out in a single four-dimensional whole.

When Cooper falls into Gargantua, the black hole, he’s pulled into what the film calls the tesseract, a 5th-dimensional construct built by “future humans” (or evolved beings). Inside it, time is laid out spatially, so he can move through moments in his daughter Murphy’s bedroom the way we move through space.

The movie’s ultimate premise is not just relativity, but love—love as the gravity strong enough to bind slices of time when nothing else can. It’s melodrama, for sure, but it still brings me to tears when I rewatch it for the eleventh time.

And that vision resonates with what the science itself suggests: the links across time may be far stranger, and far more enduring, than we tend to imagine.

And if Interstellar makes the block universe more intimate through love, Arrival might be the most faithful depiction of it in American cinema.

Amy Adams plays a linguist tasked with decoding the language of the heptapods, the alien species that has just arrived on Earth. World leaders assume they’ve come with a weapon, but what Adams discovers is that “weapon” is a mistranslation.

What the heptapods are actually offering is a gift: their language itself. Having long since moved beyond linear time, their language is circular—every sentence already complete before it begins, reflecting their non-linear view of reality.

As Adams learns their language, her perception shifts. She begins to see her daughter’s birth and death as an indivisible whole, with love and grief collapsing into the same recognition of inevitability.

Adams portrays this as a mother’s embodied knowing—the block universe viscerally embedded into her body, her grief, her stubborn love, and her refusal to turn away.

The beauty of Arrival is that, despite being an alien movie, it frames the block universe as fundamentally human: the choice to embrace all the slices of time, even the unbearable ones.

Choosing to raise your daughter with infinite tenderness, all while knowing she will die too soon, and it will destroy you.

To say yes to love, knowing loss is built in. To live as though the loaf is already whole, because it is.

And to dare yourself to act like it.

What you can taste for yourself

If all of this feels like it’s breaking your brain, that’s exactly the point. Relativity is hard to picture, and the block universe is harder still. Fortunately, you don’t need equations or alien calligraphy to taste it—just a few minutes of honest attention.

You might try this for yourself. Close your eyes and recall a specific moment from the past. Watch how it arrives not as the event itself but as a mental construction: a visual image in the mind’s eye, an echo of internal sound, or a bodily feeling that resurfaces.

Now shift toward the future. Notice how it shows up in the same format—your mind rehearsing a conversation, visualizing an outcome, spinning a scene of worry, or fantasizing about a possibility. However vivid (or vague), it still only appears as a mental image, inner sound, or bodily sensation.

Then turn to what you call the present. Attend to the breath moving in the body, the rumble of a passing truck, or the birdsong outside the window. Each impression disappears the moment you try to hold it, instantly replaced by the next. Even “now” dissolves into a flux of sensory events, with nothing solid to grasp.

What doesn’t change is the knowing itself, the simple capacity that keeps receiving whatever appears.

It’s always immediate, like an unseen gravity holding everything together.

And that unshakable capacity—awareness or consciousness itself—has always pointed in the same direction.

This is why mystics have long said time is an illusion. Einstein showed it through equations, contemplatives through attention, our culture through myth, and I’m just over here bloggin’, trying to keep up. The joke, of course, is that there’s no “present” to keep up with, which is exactly what our best science and spirituality suggest.

And yet this is where it becomes useful. If past and future are only thoughts, then most of what we call “life” is just an endless bread-slicing project in the mind—constantly replaying what already happened or rehearsing what might, clenching up against both. That is where the suffering hides, always a move away from the freedom of the present.

Nothing about reality itself has changed. What changes is how tightly we hold it.

The practical side of eternity

It’s tempting to stop here and say that all there is is the “Deep Now.” But that would be a regressive kind of spirituality, one that ignores the polycrisis we’re living through, as if the culture and climate will heal themselves if we just breathe deeply enough. Planning and collective imagination still matter, because the future still requires care.

And yet when you turn to direct experience, all you ever meet is the present. This is the paradox the block universe helps us understand:

Every slice of time already exists, but you only ever get to eat one.

Which raises the obvious question: what the hell are you supposed to do with that information? If the future is already written, does anything you do matter? Should you stop filing your taxes? Should you skip breakfast because, cosmically speaking, you’ve already eaten every egg you’ll ever eat?

Probably not. Though for the record, I’ve been skipping breakfast for a decade with great results.

What you can do is start with the practical. Stepping into this mystical–scientific view can radically shift how you meet the most basic struggles of being human, such as:

Anxiety. Makes no sense here. You’re basically arguing with physics, trying to out-think a future that already exists. From where we stand, we don’t know what’s coming—that’s why we prepare and act. But worry doesn’t change anything; it only makes you suffer twice. Drop the worry, and you can act cleanly, without hauling fear along for the ride. The liberation is meeting the future with far less stress.

Regret. The mirror image of anxiety, replaying a past that can’t be changed. It’s like picking up a history book and shouting, No, this shouldn’t have happened! But the ink’s already dry. Beating yourself up won’t change history; it only drags it into the present. The liberation is knowing the past is complete, and you’re free to stop rereading it.

Control. The same con. We grip as if the universe were waiting for our approval. But it isn’t! Your effort still matters, but the frantic edge—the resistance, the belief that everything hinges on you—is optional. The liberation is action without strain, doing what’s yours to do without being shackled to the outcome. What can follow is a kind of deep exhale.

Grief. From where we stand, the past is gone. You can’t walk back into a hug or hear the laugh again except in memory. That’s what grief most often feels like: absence. But in a block universe, death doesn’t erase what was lived. Every moment with someone you loved still exists in spacetime. The pain is that you can’t re-enter it. The liberation is knowing it’s not lost because love remains permanent, even when physical access is not.

Psychologically, these aren’t isolated struggles. Anxiety, regret, control, and grief are all variations of the same process: the mind trying to manage time in order to escape the discomfort of the present.

But that’s only the surface…

The deeper weirdness

The block universe has far stranger implications once you follow it all the way down.

The first is free will. If every moment of time already exists in the loaf, then what you call a “choice” is just the knife landing on the next slice. For many people, this realization can feel deeply unsettling. If the future is already happening, then what’s the point of trying? Should you just sit back and watch it all play out?

From inside the slice, though, it still can *feel* like you’re choosing. That sense of agency certainly feels real enough in your nervous system. But at the level of the block universe, the outcome is already happening somewhere in spacetime, which is why many physicists dismiss free will altogether. Others suggest it’s simply the subjective experience of inhabiting one slice from the inside.

Contemplatives go further, pointing out that the “you” making the choice is itself just another construction—an appearance in the mind, no more solid than the thoughts of past and future that surround it. From that view, the whole debate about whether you “really” have free will is probably less important than it seems. You keep acting and showing up.

When I first began to investigate this, it was quite unnerving—especially since I once thought I had free will figured out. But over time it turned into something freeing, even playful, like fun mystery you get to live inside. Fortunately for us, free will doesn’t need solving. It’s just life, happening on its own.

The second is psychic phenomena: déjà vu, prophecy, telepathy, etc. These are the kinds of moments that make one question the materialist consensus view of reality. If all of time is already happening inside a single four-dimensional field, then what we call intuition or foresight may just be awareness brushing against a different part of it. A prophetic dream is simply the mind wandering into a room you haven’t opened yet.

Advanced meditators and mystics have long reported such feats that boggle the mind: recalling past lives, seeing events in dreams that later unfolded, reading other people’s thoughts with sharp clarity, and much bolder claims, trust me.

Even in ordinary life, we see glimpses of it. My mom, for instance, has a knack for calling right when something big is happening with me across the country—we always joke it’s her “ESP,” a kind of motherly embodied knowing not so different from Amy Adams in Arrival.

From the outside, these claims may sound supernatural. But within the block universe frame, they could simply be what it feels like when consciousness slips out of its usual constraints and rejoins the four-dimensional field rather than just staying in the localized slice we normally inhabit.

This was actually Shamil Chandaria’s suggestion when he first introduced me to the block universe: that predictive psychic phenomena might not be “woo” at all, but the natural consequence of awareness stretching beyond its ordinary limits.

Seen this way, mystical reports of clairvoyance or the Akashic Records might just be different languages for the same capacity: consciousness opening up to itself in a way that can taste the totality of time. To be clear: physics doesn’t prove these experiences, but it doesn’t rule them out either.

The danger, of course, is chasing these powers as if they were the point. That only becomes another form of grasping. The takeaway can be much simpler: to notice that every moment you fear, crave, or long for is already present, already woven into the universe—and that you don’t need to go anywhere special to find it.

This slice, this holy now

By now you might be picturing the universe as some vast 4D object, a kind of cosmic museum where every moment is already on display. But that’s still just an image, a mental diagram we lean on because the truth is impossible to visualize.

Some physicists today argue that time and space aren’t fundamental at all, but properties that arise from how we interact with the world. The universe, in this view, is less a solid object than a quantum field. And it’s a field you can’t picture, because it isn’t really a thing—just potentiality bursting into form, faster than anything imagined, moment by moment, in this wild flowering of creation.

Contemplatives say much the same from the inside: past and future appear only as thoughts surfacing in the present, momentary ripples out of what the Buddhists call emptiness, which is best understood as potential (rather than purely “nothingness”).

So when physicists or mystics talk about an “infinite block universe,” they don’t necessarily mean endless miles of space. Here infinity doesn’t just point to vastness but to the source of all life: the inexhaustible creative void out of which everything keeps appearing.

This again is where the invitation can turn practical. Even if you can’t conceptualize any of this, you can still experience it. And if you’ve made it this far, you can notice what this perspective does to your body, mind, heart, and even your spirit. Does it make you afraid? Apathetic? Slightly unmoored?

Or maybe, I hope, it opens a different door—one of freedom. To let you glimpse that this moment is already holy, and if there’s anything worth worshipping, it’s the wild, unrepeatable mystery of being consciously here at all.

And when you look in this way, love transcends sentiment and begins to reveal itself as structural. It’s what lets Michelle Yeoh finally meet her daughter in EEAAO without running from the chaos. It’s what carries McConaughey’s Cooper through the tesseract back to Murph in Interstellar. It’s what allows Amy Adams in Arrival to embrace both the birth and the loss of her child. Love is the gravity that bends time into something bearable. And apparently, the secret to unlocking spacetime is learning to love your daughter, which is a pretty damn good metaphor for our time.

Love, acceptance, opening. Thank you for writing this in a pace that allowed me to stay open and to accept that love is always safe. It can lead to weird places, I can feel lost, dizzy and scared, but in the end love is what holds me and the bread together. That which distinguishes between life and death. Thank you, lovely writing.

Great piece Alex, read it in one go and it resonated so much. Especially as it relates in my case to helping to save and care for my daughter, which ultimately led me to experience an ego dissolution and “see” the bigger picture.

So this last line of yours, “And apparently, the secret to unlocking spacetime is learning to love your daughter” is literally what happened in my case. (No wonder Interstellar and Arrival are both in my top 10 movies ever.)

And maybe less important, but want to say it, because as an adolescent I attached a lot to the “truth” of it, is that “psychic” phenomena or things like predictive dreams, have become not-weird. I also don’t have a dog in the fight in proving or disproving those things. When they happen I just notice them with a kind of smile and let them go like another sensation or event. Those phenomena feel insignificant compared to the higher truth, which, to me, is love. ❤️