Addiction & Ayahuasca

A Vine for Troubled Times

It hurts to be a human. It always has, likely always will. Yet the perils of modernity—our endless distractions, same-day-delivery culture, excessive individualism, and overall absence of meaning—magnify one’s sense of madness.

Those who suffer from substance abuse disorder are particularly sensitive to these cultural features. They are humans who acutely feel the weight of their own troubles along with the burdens of a deranged collective.

Eventually, a burgeoning addict’s pain becomes so great, they need a way to disconnect from themselves—rapidly. They’ll do anything to find the Relief, Escape, or Belonging they so desperately crave.

Drug and drink become the solution to this scorching predicament. A “maladaptive” one, perhaps, but effective nonetheless, especially when paired with today’s cornucopia of numbing agents. Even “classic” drugs have taken on a sinister modern twist: harmless-seeming alcoholic seltzer, wildly potent engineered cannabis, and smooth nicotine vapor. There’s an even more sophisticated menu of popular pharmaceutically-engineered fixes: benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax), opiates (e.g., OxyContin), and amphetamines (e.g., Adderall). And I’d be remiss to not mention a few other contemporary drug dealers quietly turning millions into addicts of the “high-functioning” variety: Instagram, PornHub, and DraftKings. Post-industrial society seems designed to turn us all into disembodied, mindless addicts.

Despite addiction’s pervasiveness, if we take a sober assessment of the current state of treatment options, a grim picture develops. Only an estimated 10 % of addicts ever receive treatment; for those that do, the success rate is abysmally low. While helpful to many, peer-reviewed studies suggest that self-managed 12-Step programs (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous) have just a 5-10% success rate. Figures vary for rehab, but even generous estimates for long-term recovery range between 12% for outpatient and 20% for inpatient programs.

When more people are overdosing than ever, when numbers untold are succumbing to “functional” addiction during a global pandemic, and when modernity’s treatment options fail us, we must be willing to look elsewhere for answers. Troubled times require drastic solutions.

Ironically, when we look to the ancients—studying their healing rituals as old as Time—we spot glimmers of hope emerging in an unexpected form. It appears one of the best ways to quit the insanity of drug abuse is by taking … yet another “drug.”

Much has been written about the promise of psychedelic treatments. You’ve maybe even heard of Rolland Griffith’s landmark study out of Johns Hopkins University, where over 67% of participants who took magic mushrooms (Psilocybin-assisted therapy) were able to successfully quit tobacco. The Psychedelic Renaissance is well underway, and by this point, every major publication has covered and even hyped it.

But less has been dedicated to the potent approach of using ayahuasca—a psychedelic sacrament brewed from plants indigenous to South America—to combat all forms of modern addiction.

In my experience, ayahuasca—when done responsibly in a supported setting with trained experts—is one of the most powerful ways to repair the connection with the Self, restore a sense of personal sanity, and promote long-term recovery.

Addiction is a biopsychosocial condition, meaning that it stems from and impacts our physical biology, psychological makeup, and social circumstances. Ayahuasca can uniquely address all three of these complex factors.

Far more involved than the simple ingestion of a plant or pill, “sitting in ceremony” with ayahuasca includes cleansing diets, communal rituals, mystical encounters, psychological integration, and a purgative, non-addictive psychoactive tea. The impact, too, is holistic: it touches the whole human. By immersing them in a practice lightyears from the default modality of modern life, ayahuasca accelerates an addict’s recovery, helping them confront the deeper unresolved pains they must all eventually face.

I’m writing this because ayahuasca has been personally invaluable. I’m also writing this because I find it challenging to find trustworthy resources on the subject. As the Psychedelic Renaissance unfolds in real-time, social media is ripe with influencers playing dress-up as sexy indigenous shamans, misinformation, capitalistic actors, and plain narcissists. This is the essay I wish I could have read when I was in early recovery, weighing the option of ignoring my AA friends’ stern warnings that drinking ayahuasca would be considered a relapse.

This is an opinion piece. It’s my best—albeit lengthy—attempt at distilling what I’ve learned from many years of training with indigenous lineages with whom I consider to be credible, legitimate practitioners. This is not medical advice.

A few more short, crucial disclaimers: ayahuasca is not for everyone. It’s especially not for everyone suffering from addiction. All psychedelics carry risks. There are many Roads to Recovery, and I like to think of myself as a non-judgmental advocate for numerous paths and modalities. Our addicted world needs all the help we can muster. And no one solution fits all.

But this solution fit me, and I think it could help many more.

A Legitimate Path to Recovery?

First and foremost, the decision to drink ayahuasca is complicated for someone who has earnestly dedicated themselves to recovery. There are many conceptions about what recovery is, and what it is not. For some, sobriety is attending a recovery meeting every day while chain-smoking cigarettes, drinking five coffees a day, and taking a sleeping pill at night. Many still consider drinking ayahuasca a relapse.

These narratives should be heard, processed, and potentially ignored.

In the same way I would not describe military training as a “shortcut” to physical discipline and building team spirit, I would not characterize ayahuasca as a shortcut—it’s a brutally intense short-term education.

The entire process is measured, deliberate, and often painful.

Part of ayahuasca’s beauty lies in its open-minded nature. Ayahuasca can be a helpful companion to 12 Step work, as my friend and colleague Todd Youngs elegantly describes in the article Ayahuasca and the Twelve Steps: An Anonymous Friendship.

Ayahuasca can also be a refuge for those seeking alternative experiences, for those who get triggered by what they perceive as outdated religious language in the 12 Steps.

For some, ayahuasca has a powerful spiritual or even paranormal dimension. I’ve previously written about having an alien baby expunged from my belly during one profound ceremony in Peru. I’ve encountered an intelligence and indescribable beauty that made me, a former atheist, ponder my maker.

But, while I cannot under-emphasize the importance of all these experiences for me, I also can say that one does not require any Terrence McKenna-like revelations in order for ayahuasca to be an effective recovery tool. Ayahuasca does not care where your specific recovery paradigm might fit into this mix. All that it seems to ask is that you show up with as clear a mind and heart as you can muster.

For us addicts, all that matters is whether we’re progressing our recovery, or not. What matters is the results.

After drinking ayahuasca, my creativity exploded. My nutrition and consumption of animal protein became far more intentional. Meditation, yoga, and indigenous rituals became pillars in my life. I worked up the courage to begin publishing my writing in earnest, leading to building a following of thousands of readers, like you, some of whom take the time to read 5,000 words on this niche subject.

But perhaps most importantly, today I feel further away from a desire to take my drugs of choice than at any point in my life.

“I am certain that the LSD experiment has helped me very much.” —Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, in a 1957 letter to philosopher Gerald Heard

So, when people in recovery who are new to ayahuasca ask me about it, I typically don’t get into the extraterrestrial encounters and cathartic purges we’ll explore in this essay. I focus on the life-changing results. I tell them that ayahuasca was a rite of passage that uncorked the latent potential already dwelling inside me.

Supplemental Medicine versus Rite of Passage

Traditional allopathic medicine is often thought of as supplemental: go work, make money, then spend some of that money on therapy, and maybe take this pill.

In contrast, ayahuasca is not just a supplemental medicine. As you’ll see in the following pages, when all of its components are totaled, the experience amounts to a paradigm-shifting rite of passage. It requires tremendous courage.

And, short of joining the Marines or removing oneself to a Buddhist monastery, such a shift is nearly impossible to find in today’s society. Even attending inpatient rehab, sheltered away from all of modernity’s temptations, can feel more like a structured furlough rather than a rite of passage.

For the modern addict, approaching ayahuasca as a recovery tool allows for a new biological, psychological, social, and spiritual narrative to be written. It allows for the creation of a whole new You.

And despite gospel from outdated notions of recovery, it can do so without compromising one’s “sobriety.”

Of all the Psychedelics, Ayahuasca Might be the Least Addictive

Ayahuasca is the anti-drug. Called the “the medicine” by initiates, it is a non-addictive compound.

First, it tastes like a dreadful mixture of licorice and mud, a far cry from the delectable aroma of Patrón, my (former) Latin American drink of choice.

Secondly, ayahuasca is typically swallowed in a ceremony setting, administered by a shaman or guide. Hard to binge on those.

Third, it makes you throw up. This is known as “purging.”

Fourth, the entire experience is often ferociously intense. Like anything psychedelic, there are times when the journey can be elevated and blissed-out like, dare I say, a high. But any highs are often accompanied by terrifying lows. After a night of throwing up and reckoning with shadows, most people are not quick to come back. They might even shudder at the thought, as I did after participating in my first ceremony.

Fifth, unlike other substances, ayahuasca typically has a “reverse tolerance,” where the more one drinks it, the more sensitive they become to it. Ritual users of ayahuasca do not develop a physical tolerance.

This brings us to the sixth critical component about ayahuasca and addiction:

You cannot “score” ayahuasca on the corner of Turk and Leavenworth in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, where I used to procure virtually every other addictive drug known to humankind.

You’ll also be hard-pressed to find ayahuasca at a Phish concert, where you can, in abundance, find magic mushrooms, MDMA, ketamine, LSD, and even smokable DMT (which is a short-lived drug that should be considered an entirely different category than ayahuasca, which is a sacrament). As someone who can attest from experience, all these other psychedelics have the potential for abuse by a motivated addict.

For these reasons, ayahuasca’s potential for repeated consumption is extremely low; even those who are at risk of abusing psychedelics will find it difficult to develop an ayahuasca addiction, due to its intense, retreat-oriented, ceremonial nature.

Also worth noting: the only other psychedelic impossible to procure on skid row with similarly non-addictive tendencies is iboga (Tabernanthe iboga, indigenous to Central Africa), which is currently used to treat opiate addicts and has great anti-addiction potential.

Yet, if ayahuasca is the Mt. Everest of psychedelics journeys, iboga would be K2—the far more technical and difficult climb. An iboga journey can last for up to 48 hours (!), and often requires medical supervision.

So while some psychedelics are helpful for combating addiction, in my assessment, ayahuasca is not only the safest, it’s the most intriguing …

Ayahuasca’s Ancient Origins

Depending on your disposition, ayahuasca’s discovery was either a coincidence or an act of God.

Ayahuasca is indigenous to the Amazon basin, in the wild lands of Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Out of a rainforest filled with over 80,000 species of plants, ancient shamans somehow discovered that when you brew the ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) with the chacruna leaf (Psychotria virdis), the result is one of the most powerful entheogens known to humankind (entheogen = naturally occurring plant-based psychedelic).

The chemistry allows for the active ingredient, DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine), to become orally active. DMT is a fascinating compound endogenously produced in most living organisms. While we know DMT exists in humans, its exact function and purpose in our bodies/brains remains a mystery. Scientists know DMT is released during birth, death, and even during deep REM sleep, which helps explain reported transcendent experiences during all three. For these mystifying reasons, researchers have dubbed DMT the “Spirit Molecule.”

To this day, the sophisticated pharmacology displayed by indigenous shamans in creating ayahuasca baffles scientists. The odds of matching the chacruna leaf (which contains DMT) with the ayahuasca vine (which contains monoamine oxidase inhibitors—MAOIs—to allow for the DMT to be digested) are slim to none. With so many combinations of plants to boil together, how the hell did shamans decide to boil these two? The odds are so slim, many ethnobiologists take indigenous healers’ explanations to heart:

The shamans say that they learned how to create ayahuasca directly from the plants themselves, by attuning themselves to the intelligence of the natural world.

There’s evidence that ayahuasca has been used in South America for approximately 1,000 years. But it likely goes back further—the jungle isn’t friendly to archaeologists, swallowing up drinking vessels and ceremonial tools, making evidence difficult to come by. Some researchers believe all civilizations emerged from the Amazon basin tens of thousands of years ago, and that ayahuasca likely played a pivotal role in the development of consciousness. We do know, for certain, that it has been used for centuries in indigenous healing rituals to cure a variety of suffering from distress to disease.

An Ancient Brew for Modern Malaise

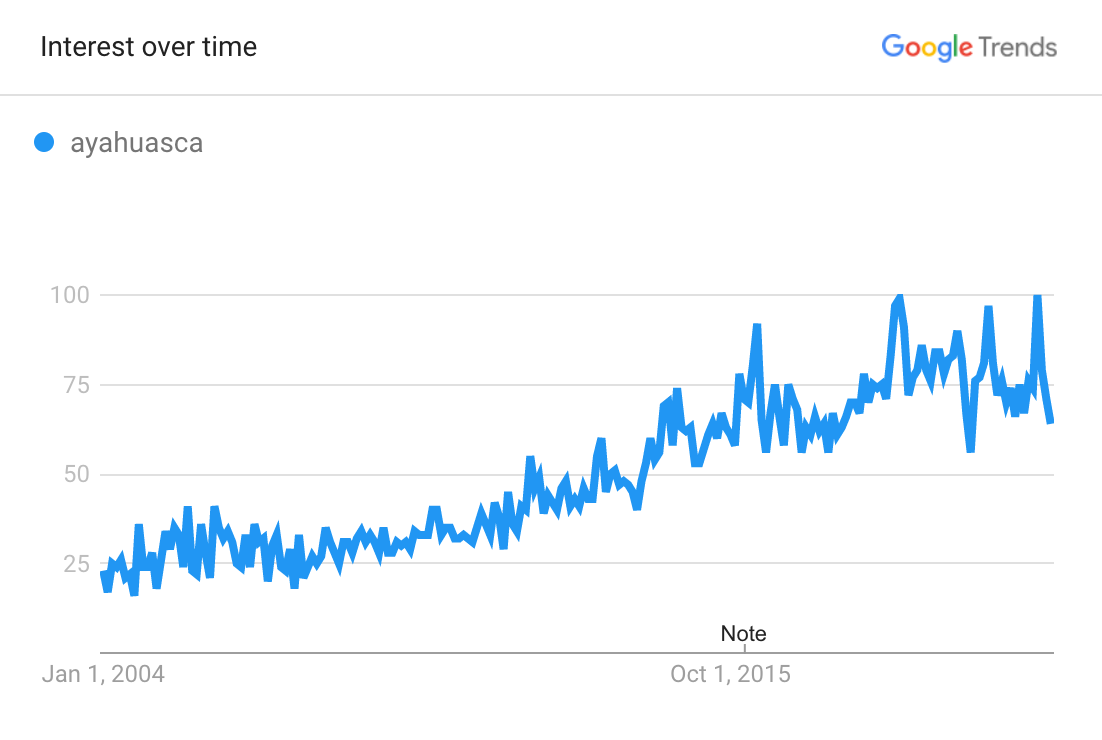

The fact that ayahuasca is a naturally occurring healing agent provides an important context for where we find ourselves today. As we wage war on our biosphere, as Diseases of Despair (addiction, alcoholism, suicide) skyrocket to peak levels, and as chemical dependency spirals out of our control, it seems ayahuasca wants to rise.

A literal interpretation of ayahuasca’s ascent would be that the Psychedelic Renaissance has popularized an indigenous practice previously only reserved for First Nations people and the most adventurous Westerners.

The figurative interpretation, which is the leap of faith I find solace in, is that ayahuasca has an ancient agenda connected to Mother Nature and healing. Plants are conscious beings. We have co-evolved with them: thousands of years ago, they whispered into shaman’s ears, quietly telling them to use this brew to heal their wounded. Now, these whispers of ayahuasca’s healing are uttered in books, magazine articles, trippy podcasts, social media posts, and healing communities around the world. Ayahuasca is knocking on our door. It’s spreading because we need it.

Whatever ayahuasca’s agenda is, it allowed for a random, insecure Jewish kid with a hefty drug problem to find his way to the jungle and into its arms. An experience that convinced me the holistic experience is not only safe, but uniquely compelling for recovering addicts to explore.

The Dieta: Cleansing a Ravaged System

The ayahuasca experience starts long before you drink the medicine. For an addict or non-addict alike, one of the most powerful elements of the experience is la dieta, or the cleansing diet. It’s easier to metabolize ayahuasca with a clear system, which is why indigenous shamans prescribe eliminating meat, spicy foods, sugar, sex, and negative or stressful stimulation (bye bye, Game of Thrones) to prepare your mind and body for the journey.

You do this to cleanse your system and prevent uncomfortable interactions from the ayahuasca itself. For most of us, following the dieta is an intense habit change, helping us transition into a state of intentional healing. The process is far deeper than gobbling some magical mushrooms on a Friday night with friends.

Most importantly, you must eliminate intoxicants—ideally for at least two weeks before the journey. This means, in theory, no one is showing up to an ayahuasca ceremony after a week-long cocaine-and-Tito’s rager. Or, signing up for outpatient treatment the day after taking your “last and final” oxy and D-amphetamine and cocaine bender, like I did, on several unfortunate occasions.

For many addicts, the dieta might be the first time in their lives when they begin to properly pay attention to what they are putting in their system. It serves a vital psychological function, forcing a participant to closely monitor their diet, caffeine and depressant intake, and overall health.

To put this in recovery terms: ayahuasca is like attending an outpatient detox program and then having a 12th Step—a spiritual awakening—scheduled on the calendar.

The Purge: Changing Spoiled Oil

After several weeks of conscious eating and intake, an addict’s nervous system has been essentially enjoying a bubble bath, their liver especially relishing the relief. On the day of the ayahuasca ceremony itself, the dieta prescribes fasting for 4-6 hours before the ceremony, so that the sacrament can be met with an empty stomach.

But! Despite having a vacant stomach, purging is almost always part of the ayahuasca experience. While the idea of vomiting is dreadful, the purge often feels quite cathartic. Like taking all your baggage, compressing it into a shipping container, and ejecting it into space.

From a literal standpoint, the purge cleanses toxins from the stomach, helping to rebalance the gut biome (and the New Age loves rebalanced gut biomes!). I cannot stress how important the purge is for an addict to experience. After years of punishing their bodies with chemical neurotoxins and poor nutrition, all addicts are overdue for an oil change.

Yet ayahuasca always touches the metaphorical as well as the literal, and the purge is where the mystical squarely enters the frame. Purging on ayahuasca is purifying on an inexplicably energetic level. Shamans claim that the purge literally dispels negative spirits, evil spells, past traumas, and unnecessary psychological burdens. I’ve seen people who have fasted for a week before an ayahuasca ceremony—with literally nothing in their stomach—puke their brains out over the course of an evening, filling up entire buckets with dark, thick, liquid … energy.

I then watched them emerge as fundamentally changed people.

For a deeper explanation of the art of ayahuasca shamanism, read this book by Dr. Joseph Tafur.

An Ego-Destroying Journey

Most ayahuasca journeys take place in the evenings, covered by the blanket of darkness. Participants lie on a mat on the floor, listen to the curated music, and do their best to let Grandmother Ayahuasca—known as Abuelita—heal them. (Other indigenous lineages call it Grandfather Yagé, known as Abuelo.) The ceremonial intimacy becomes a direct route to stare one’s demons directly in the face, with nowhere else to go or hide.

Addiction is merely one facet of the diamond of consciousness. It’s a manifestation of deeper unmet needs, a coping mechanism to prevent us from feeling buried, scarier pain. Whether one’s malaise is addiction, depression, anxiety, or even autoimmunity—there’s typically a deep-seated psychological signature underneath the experience. In this way, drug addiction is merely a strategic way to keep the wounded part of us safe.

To understand the psychology of an addict’s behavior, we must loosen the tight bonds of the Ego’s grip. Most psychedelics do this effectively, but tryptamines—the type of psychedelic classification of DMT—are known to be especially ego-destructive. Ayahuasca has a way of dissolving everything that an addict has been conditioned by over a lifetime:

Your name, physical appearance, sexuality, job, drug(s) of choice, and the number in your bank account all suddenly become less important, dissolving into emptiness.

An Ego Death can be a delicate, terrifying experience, which speaks even more to the importance of being guided and held by trained experts. When the Ego takes a backseat and, finally, allows an addict to look deeply inward, they are often faced with all of the things they’ve been unwilling to see.

Ayahuasca is a pattern interrupter. One by which an addict glimpses their existence from a bird’s eye view to see how they’ve (mis)constructed their reality, and allows for a catalytic realization to emerge:

Things can be different. A new way of living—without drug or drink—is possible.

A Curative Mystical Experience

“His craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God” —Carl Jung in a letter to Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, 1961

Ayahuasca’s spiritual component is perhaps its most profound, wonder-dipping facet.

It is called “The Vine of the Soul” because shamans believe it directly connects a person with their formless, timeless essence—what the Hindu’s call the Atman, the Quran calls Rūh, and what Judeo-Christian traditions simply call the soul.

And here’s where things start to get even more … otherworldly. In contrast to other psychedelics (non-tryptamines), drinking ayahuasca often includes connecting with intelligent entities, or spirits. It’s extremely common to encounter animalistic spirits, like serpents, birds, and jaguars. DMT journeyers—myself included—often report connecting with wholly conscious entities—like aliens, intelligent jesters, mind elves, and little doctors (doctorcitos). These “spirit doctors” often perform a type of psychospiritual surgery, literally expunging negative thought patterns and trauma from the psyche.

Sound nutty? Maybe. Yet cutting-edge researchers are currently attempting to study the conscious “entities” common to the DMT experience, even hoping to dialogue with them to better understand the nature of our multiverse.

It is true that when fifteen people drink the same ayahuasca on a given night, they will have fifteen different experiences. However, most report connecting with a spiritual intelligence greater than themselves which, interestingly, helps them realize that same intelligence must dwell within them.

The use of psychedelics to treat addiction is not new. In the 1950s, the psychiatrists Humphrey Osmond and Abraham Hoffer ran studies with LSD on thousands of alcoholics, finding a strong correlation between the intensity of a participant’s experience of “transcendence” and their chance of subsequent recovery. (Osmond also famously gave Aldous Huxley his first dose of mescaline inspiring The Doors of Perception, coined the term “psychedelic,” and introduced Bill Wilson to LSD.)

Awakening to a sense of mysticism and spirituality can become a vital part of one’s recovery from addiction. Ayahuasca’s orally active, multi-hour DMT journey is a rocketship into these divine realms.

In my case, ayahuasca freed me from the clutches of a disembodied existentialism—a worldview I clung to since college. It had convinced me that rugged individualism was the only solution to the apparent meaninglessness of life.

I was someone who loved knowledge and could rattle off academic philosophies. But during my first ceremony, I encountered a type of mystical, hyperdimensional, and timeless wisdom that I knew nothing about. Nothing has been the same since.

Witnessed and Held by Community

There are many theories about addiction, but they all agree that restoring a sense of healthy community is central to sustaining recovery.

Some addiction writers, like Johann Hari, believe addiction is a result of a lack of connection. Other addiction experts, like Dr. Gabor Maté, believe addiction to be the outgrowth of unearthed childhood trauma. Before the Canadian government slowed his programs, Dr. Maté worked to address this disconnection through group ayahuasca retreats for addicts, providing a corrective emotional experience.

Crucially, ayahuasca is done in a group setting, with circles ranging in size from four to one hundred participants. The typical size is about twelve individuals. At any one point in the evening, an ayahuasca ceremony might sound like visiting the floor of a mental ward. People will be crying, laughing, vomiting, sobbing, and moaning. The full spectrum of human experience is contained within these ceremonies, where participants witness every aspect of the psyche laid bare.

As such, each person holds a dual role: they are both a participant and witness. As they face their own darkness, they simultaneously hold space for others to do the same.

While individually guided psychedelic journeys are potent, I believe the communal aspect of ayahuasca—as practiced in indigenous societies—is particularly effective for addicts. Drugs often pull addicts into isolation—or, towards others similarly afflicted. Aligning to an open-minded, recovery-focused community is paramount. It’s also the byproduct of sitting in a ceremony, where participants walk away with lifelong, unspoken bonds.

Embracing Ritual and Ceremony

Many people associate psychedelics with friends dropping acid on a camping trip, frolicking around hills, laughing around a campfire—or, experiencing a dysregulating “bad trip.” Modern psychedelic-assisted therapy conjures a different visual: a sterilized office environment, eyeshades, noise-canceling headphones, and a gentle therapist holding a journeyer’s hand.

Ayahuasca, which is a ritualized sacrament, is quite distinct from all of this. It embraces ceremonial rituals, the specifics of which can vary depending on the numerous South American tribal lineages such as Shipibo, Quecha, and Kamënstá. However, most ceremonies involve a beautifully specific order of burning plant resins, sitting in shared silence, harmonica and drums, healing songs, dancing, and prayer.

There are many essays, even books dedicated to the disastrous consequences of the lack of ritual and rites of passage in Western society, such as the lack of personal agency, boys who never psychologically grow into men, women who emotionally remain girls, and group-think tribalism and distrust.

Addicts are uniquely sensitive to these consequences. Their only source of ritual is cracking the post-work Bud Light, or the routine of chopping up opiates into neat, snort-able lines in a bathroom stall, as was one of my customs.

Traditional rehabs have routines, disciplines, and even spiritual practices. But nothing quite like sitting in a candle-lit ayahuasca ceremony, participating in an ancient ritual designed to organically transform lives.

Integrating Shadows and Insights

Actually, drinking the ayahuasca is just the beginning.

As Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), constantly reminds people, it’s not just the drug that produces the results—it’s the therapy, aided by the drug.

Or, like one of my teachers reminds us each morning: the ceremony is the easy part.

Ayahuasca, when done responsibly, involves weeks of preparation, and then, finally, the actual ceremony itself, in all its thunderous joys and terrors.

The integration process is especially important for Westerners, who at times can have trouble contextualizing a shamanic experience loaded with holographic visions, spirits, and insights. For a recovering addict, this is when they can begin to piece together the many parts that led to their addiction, process extricated traumas, and then come up with a plan for sustained recovery going forward.

Just one ayahuasca ceremony can provide insights that last a lifetime. The challenge, however, is remembering these transformations fives days later when you’re stuck in traffic, already late for your next meeting, experiencing all of life’s triggering minutiae.

This is why responsible ayahuasca communities and retreat centers offer a plethora of integration activities following a journey. Hopefully, in the weeks that follow a journey, these days, an addict will likely be processing the experience with the ceremony facilitators, peers, therapist, coach, or—as is becoming increasingly common—an open-minded 12 Step sponsor. And on top of that, there are now programs like Psychedelics in Recovery that provide free integration meetings for addicts following similar paths of intentional recovery. These integration activities are not to be skipped.

Reciprocity and Thoughtfulness

Also not to be overlooked: ayahuasca is an indigenous medicine, meaning it’s crucial to consider and reciprocate the First Nations communities in the Amazon basin where these powerful practices originate.

Appropriation—taking ayahuasca practices out of their contexts and profiting from them—happens far too often. Ayahuasca’s popularity has also left it overharvested, straining the supply in tribal communities.

Interestingly, ayahuasca ceremonies are increasingly led by women. As Brian Muraresku points out, most ancient psychedelic rites were women-led until Christianity pushed these rituals to the fringes. Today, it seems the scales are beginning to balance. I can, anecdotally, attest to this, as the community I work with is entirely women-led.

The link between reciprocity, equality, and addiction is quite profound, one that postmodernity often reminds us of. Addiction is often the result of marginalization, abusive systems of power, and outdated policies like the “War on Drugs.”

As it was in my case, ayahuasca often becomes a catalyst for social change, helping people reconnect with themselves, nature, and First Nation communities. There’s no such thing as the “higher consciousness” espoused by the Psychedelic Rennaissance if we do not help those who need it most.

Some Considerations Before Your Journey

You’ve made it this far. If you’re interested in exploring this path of recovery, please keep these things in mind:

Be careful with online shopping. If you needed to have brain surgery, you would not go on Instagram to find a neurosurgeon you trust. The same should be true for ayahuasca. One of the greatest risks is landing with under-trained facilitators popularized by influencers sharing affiliate links.

Yet do your research. Like many things in life, ayahuasca has a predatory dark side. Dark shamans—known as brujos—have been known to abuse power, sexually violating vulnerable journeyers. Gringo wannabe shamans can also become drunk on their influence, nudging their followers towards delusional-prone thinking and spiritual bypassing. One should be unwilling to work with anyone other than highly praised, trained experts.

Ayahuasca has its risks. Certain medical and psychological conditions (like heart irregularities, bipolar, seizures, schizophrenia, and more) make ayahuasca unsuitable.

It can be expensive. Consider travel costs to a safe ceremony space in the US or overseas, lodging, etc. Yet at the same time, it doesn’t have to be expensive—there’s a spectrum of options from rugged to glitzy.

Ayahuasca is a fast-emerging industry. All these considerations are changing rapidly: costs are coming down, access is increasing, and laws are embracing the potency of this healing path. Importantly, scholarship-based programs are springing up to support those in need. (Stay tuned on that front!)

Lastly, the point of ayahuasca is to heal and grow. That doesn’t mean it is a magic panacea for curing addiction. Ayahuasca is simply a potent way for an addict to begin or progress on that very personalized journey. Everything that arises on ayahuasca, arises within you.

I don’t sit in ceremonies quite as frequently as I once did. During my last, which was a community camp out under the stars, I was reminiscing on my recovery and realized that ayahuasca has walked with me at every step. From helping me understand what led to my addiction, to offering me a nudge to quit my tech job and work in the addiction space, ayahuasca has guided me towards a more natural way of being. Under the starlight that cloudless evening—as I was singing songs while sitting next to many teachers and friends, communing with an intelligence I’ve come to cherish like a grandparent—I glanced up at the full moon, beaming. I knew then I had to write this essay.

Thank you for reading. Special thanks to Celina De Leon, Todd Youngs, Ja, Grace Parker-Guerrero, Sasha Chapin, and Zach Hyatt for providing feedback and edits on this piece. Y mil gracias to the Shipibo and Kamënstá wisdom keepers who graciously teach me their ways and how to attune to the rhythm of life.

If you know someone who might benefit from this essay, please consider sharing it with them.

Thank you for this comprehensive offering on a topic that contains myriad multiverses within itself, and yet is nonetheless niche and incredibly current.

I definitely get the sense that the effort you have gone to in order to present this essay in its current form is going to be incredibly worthwhile to people who need this level of context in approaching the medicine. Let's get the SEO fairies to work on it. :-)

I have not experienced the medicine myself (not out of any resistance; it simply hasn't arrived on the path) but I have come into contact with plenty of people who have affirmed this precise narrative of transformation. The caveat here, as you have described, is the need for meaningful integration of the journey through continued practice, literally building one's life up from scratch around the shadows and insights from ceremony.

A corollary thought:

Once you find Deep Fix, you cannot un-find it; it's a seed that germinates in consciousness, expanding towards the light as it is grounded in the truth of genuine and relatable experience. Thanks for taking us all on this unique and precious journey with you! ꕥ

Well that was just the best article I’ve read on ayahuasca in maybe ever! As said above, most of everything I see is a trend piece, or a warning, or so, erm, ‘out there’ it’s just not useful to me. And thank you for talking about the appropriation aspect, it’s one of the reasons I’ve not tried the vine yet (I live quite far from any centre that sounds like a respectful provider, and I’m now even less interested in just snagging some from whoever). Really, thanks.