I first learned about the UnitedHealthcare CEO assassination when my parents called from Manhattan. Like most New Yorkers that day, they were rattled by the brazen daylight killing. They were also surprised I hadn’t heard about it, but I was in my usual hardcore daytime Do Not Disturb mode, writing and sitting with clients. My dad—who shares my obsession with spy novels—and I talked through the horrifying details. Together we theorized about what type of person would commit such an act, hired assassin or not.

Nothing could have remotely prepared us for the killer to be Luigi Mangione. And as someone who studies culture, at least as a hobbyist, I knew something had shifted the moment I started learning about his story. This wasn’t just another American tragedy unspooling across our screens. Each new detail that emerged confirmed something far more significant was happening.

A valedictorian with dual Penn degrees sliding into psychedelics and self-improvement manifestos. A brilliant young mind wounded by the healthcare system who became not just a dark folk hero but, following a pattern as old as revolution itself, an object of mass attraction—his jacked physique and model-like looks sparking a twisted kind of celebrity worship online. The kind of story that shatters all our usual interpretive frameworks. In my gut, I worried Luigi was just the beginning. The first of many. Alex Beiner’s essay, the best I’ve read on the killing, called it a cultural breach event. A breach occurs when the swirling ocean of our collective online fantasies, hopes, and rage finally erupts into physical reality.

And breach it did. The case haunts us first through its metamodern contradictions, and those certainly abound: elite student becomes anti-elite killer, techno-optimist turns micro-Unabomber. But what truly grips us is what happens when the promises of elite achievement culture collide head-on with both systemic disillusionment and profound personal suffering. A young man does everything “right,” checks all the boxes, then perhaps experiences firsthand the cruelty of our healthcare system—and something breaks. When I put my cultural philosopher hat on, I see this as a preview: our terminally online culture meeting profound social frustration that’s close to erupting.

Looking deeper, this tragedy exposes something darker than just ideological certainty, that dangerous state where complexity dissolves into absolute conviction, where nuance dies and the world becomes black and white. Behind ideological violence of this nature—even when fueled by psychosis—always lies deep, unbearable pain.1

But instead of real containers and guidance for a young man with immense talent, we offer a seductive and toxic mix of anti-establishment narratives, self-help manifestos, contrarian bloggers, and an unhinged personal development culture that can send wounded people spiraling without any guardrails—all while certain billionaires and radical progressives alike cheer for the collapse of the very system that created them.

Beiner captures the tragic irony of this violence when he writes:

“If Mangione had destroyed the data centres that house United Healthcare’s patient records, it wouldn’t be a powerful breach event. But he killed a human being, a father and husband. He removed an experience from the world, as revenge against a machine that doesn’t care about experience. The assassination is a koan that brings to light the paradox at the heart of civilisation: what’s real is our experience of being alive, not how we can be quantified, but we pretend the opposite is true.”

What makes this case so haunting isn’t just its contradictions—it’s how it shatters our most basic stories about progress, success, and social mobility. Here was someone who mastered the game, only to flip the board entirely. Let’s be clear: you can’t just murder people. Full stop. When journalists like Taylor Lorenz express joy and explicitly state she feels no empathy for the killing, it reveals the moral bankruptcy of a certain progressive mindset that celebrates destruction over genuine reform. At the same time, we can acknowledge that our healthcare system systematically destroys lives while executives rake in millions, and it urgently needs to change. The tragedy cuts both ways.

Beiner’s analysis, drawing on Peter Turchin’s research, helps explain the deeper historical currents at play:

“Social strife happens when inequality spirals out of control, while at the same time there are too many ‘elite aspirants’ and not enough positions for them. Eventually, members of the elite defect (becoming counter-elites) and align with the angry masses to change the status quo.”

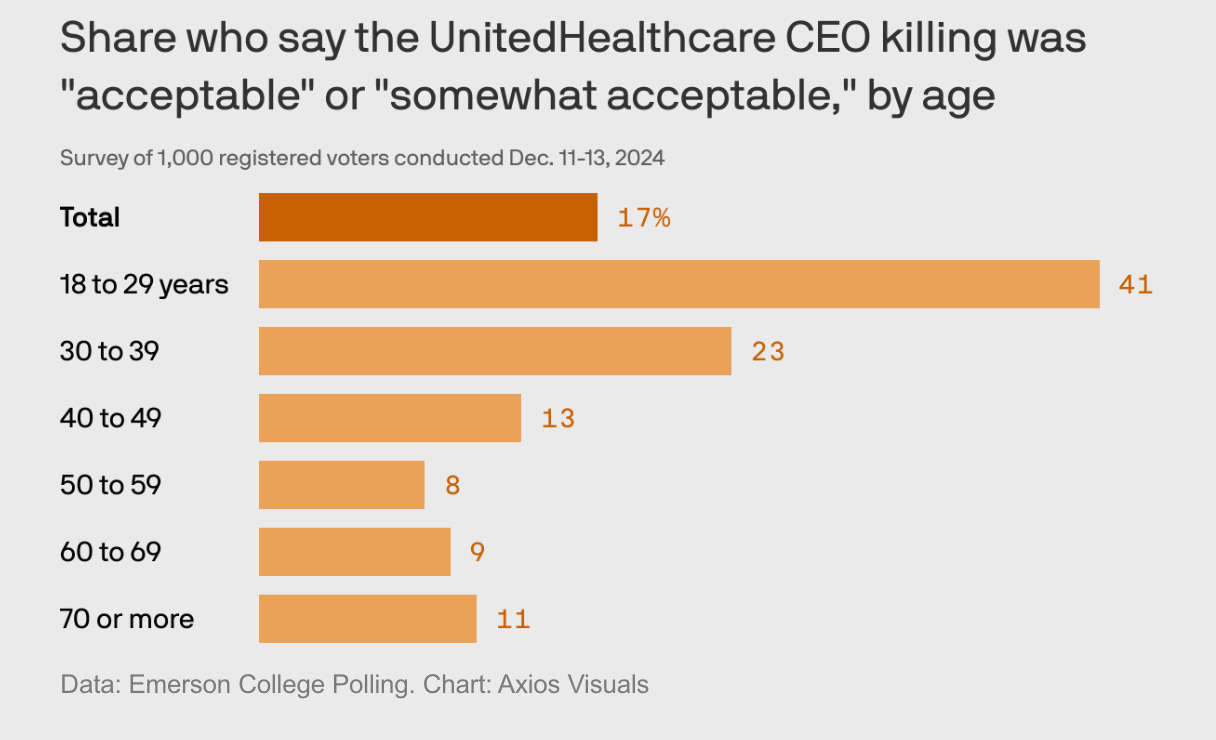

This isn’t theoretical anymore. The data reveals a seismic social fracture. In my recent essay on Trump’s inevitability, I warned about a generational shift happening right under our noses: 60% of Americans under 30 approve of the Trump transition. Now combine that with a far more disturbing data point: 41% of those under 29 approve of the UnitedHealthcare CEO killing. Let that sink in. Nearly half of young Americans see the assassination of a healthcare executive as justified.

This isn’t just about politics anymore—it’s about the complete collapse of institutional legitimacy.

And it goes beyond normal generational rebellion. It suggests a profound rupture in social trust, a generation that’s concluded the system isn’t just broken, it’s malevolent. As Daniel Pinchbeck says, history doesn’t necessarily repeat, but it does rhyme: when young people start seeing violence against elites as justified, when folk heroes emerge from acts of political violence, when the educated turn against their own system—these are the same notes that have played before every major societal breakdown in history. And once this kind of legitimacy crisis takes hold in young minds, it doesn’t easily reverse; it tends to accelerate until something fundamental breaks or transforms.

It’s easy to distance ourselves from history, to read about the French Revolution’s guillotines with a kind of comfortable detachment. The idea of crowds cheering as aristocratic heads roll feels safely archived in textbooks. But that’s just our inability to imagine the raw emotions of the time, the way inequality and elite corruption created a powder keg of collective rage. When we read about the sans-culottes, we forget they weren’t just an angry mob—they were people who had watched their children starve while aristocrats feasted.

Today’s version doesn’t need guillotines in the town square. It lives in our phones: broad daylight Manhattan assassinations becoming libidinous folk tales, TikTok edits of the killer set to techno-pop, memes that transform tragedy into entertainment. The methods evolve, but the underlying pattern remains eerily constant: elite education breeding elite resistance, systemic corruption spawning its own destroyers. But there is a crucial difference: where the French Revolution’s violence played out in public squares, ours unfolds in a hybrid space where digital celebration bleeds into physical violence.

As we map these historical similarities, at a certain point, we have to ask ourselves what to do, and how we might maintain perspective while swimming in waters this dark.

Here’s what I’ve noticed: when I’m deep in the online world, cultural events like this feel seismic, world-ending even. The digital amplification makes every breach feel like the final crack that will shatter everything. Yet when I step away—whether for a meditation retreat, a sabbath day of silence, or a year off social media—something shifts. The events don’t become less important, but they settle into a different scale entirely. It’s the difference between a surfer watching the heavy swell from the beach and being caught under the waves in the undertow.

But this isn’t an argument for spiritual bypass. Yes, offline life grounds me. Being in relationship with someone who isn’t an “online person” or creator or even lurker of discourse keeps me tethered to what’s most immediate and real. But simply retreating from these cultural tremors misses something essential. I’ve watched too many consciousness seekers—myself included at times—dismiss these types of events as mere “noise,” as distractions from the “deeper work.” We can fall into a kind of spiritual elitism that’s eerily similar to the institutional disconnect we see in healthcare executives and mega-wealthy, a way of floating above the messy reality of normal human suffering.

It’s funny, because my primary interest is dharma, in waking up to true nature and wanting that for more people. I could be writing to you about how I’ve discovered reliable methods to dramatically increase baseline happiness and dissolve the suffering around meaning and purpose—teachings I’m passionate about sharing with others. And yet I feel this deep urge, both from a soul level and perhaps from some lingering surface level attachment to drama and discourse, to help make sense of these evolving moments with you all.

These breach events, these cultural wounds—a brilliant young man’s descent into violence, a system’s failure to honor human health, our collective digital fever dream—aren’t just events to anaylze or transcend. They’re expressions of our collective consciousness wrestling with its own shadows, its own contradictions. The relative is the absolute. That’s why I write: I genuinely love making sense of these cultural ruptures, trying to understand the myths that govern our times—though I worry I’m just performing the very online-brain syndrome I’m critiquing.

As far as I can tell, the Luigi case isn’t just another story about elite education or healthcare or online radicalization—it shatters our comfortable notions of progress, meritocracy, and institutional legitimacy. Each detail becomes viral entertainment before we can process its meaning, while beneath the spectacle runs a story as old as time: the brilliant child turned destroyer, transformed by our digital gaze into a kind of sexy-Che Guevara figure, all of it playing out at hyperspeed through our digital nervous system. And maybe understanding these breaches, in all their complexity and pain, is the first step toward healing them.

Mangione’s recent writings certainly don’t suggest psychosis, though footage I’ve seen of his arrest does indicate psychological destabilization. Given his time in Hawaii, psychedelics may have contributed to an existing instability—pure speculation, but worth noting. These ambiguities, combined with some peculiarities in the footage and arrest circumstances, have predictably fueled conspiracy theories. While some claim to see obviously different people in the videos (though a facial surgeon’s analysis suggests otherwise), and the McDonald’s arrest by a worker who spotted him masked seems strange, the tendency to cry “CIA psy-op!” feels like an oversimplified response to a deeply complex case. The uncertain nature of these details doesn’t diminish the breach—it amplifies it, adding another layer of metamodern contradiction to an already trippy event.

The strangest thing to witness is how such a huge part of the US population have come together on this. There seems to be less divide on this matter than on other serious issues. Ive not seen so much unity on something in a very long time. I dont condone killing by any means but I also understand, if history tells us anything, that when broken systems desperately need to be destroyed, there are lives that also get destroyed in the process. If there was a peaceful path to cause this level of disruption then of course that should have occurred- but I'm not sure there would have been a peaceful way and this upheaval so needed to happen. The oddest part is how the collective doesnt see this as a senseless killing but rather as a murderer of innocents being brought to justice. Almost as if they're rejoicing the death of Hitler. Are these health insurance professionals becoming the modern day evil, committing eugenics by letting the poor die and the rich be healed?

Most of the systems in our society are there to oppress us under the guise of protecting us. When these seismic events happen at the hand of a fellow human, it awakens the notion of people power. Of course anarchy isn't the ideal answer and I'm sure there are many psychopaths taking notes but I have a strange feeling that this monumental historical event may be the first domino of change- although we may not see that change for a long time to come. I also understand the outrage people feel around the murder. It's not a pleasant thing but I would be interested to see a poll on what kind of health cover people had. If one feels safe and comfortable it is easy to feel outrage for the murder but I think for a lot of people who have been denied care or gone into unmanageable healthcare debt, the murder offers respite. Someone has been held accountable. I can observe and understand both sides of it. I dont think either side us unjust in their feelings.

The murder brought up such complex thoughts and feelings for me. I had to question, did I consider this CEO to be an innocent victim? And I'm still searching but I'm not sure I do. I had confront the sense of justice I felt surrounding his death even though I knew it wasn't a positive thing. It's easy to feel safe in the arms of a vigilante when you feel so unsafe in the arms of the government or the police. Since covid, the veil has dropped completely and people cannot unsee or unlearn all the corruption and lies that make our world go round. I'm not sure where this is all going but when things have hit rock bottom, and there has been no hope or optimism for so long, perhaps this will be the starting point of our brave new world.

As mentioned in other comments, I too recognize there is a nuanced perspective that acknowledges murder is wrong and inhumane while also acknowledging the failings of the healthcare system as wrong and inhumane.

It is easy to toil over the complexities of this “breach”, but for me it all boils down to love vs hate. Ted Kaczynski is an exceptionally brilliant mind (seemingly more so than Mangione based on his manifesto), but he gave way to letting hate consume him and for that he ultimately failed.

When I was younger, angrier at the world, and less in control of my mind and emotions, I used to side with Kaczynski and Mangione in their justification of violent acts. Now as I have grown older and wiser(somewhat), I believe that violence and atrocities only breed more violence and atrocities on any historically relevant timescale.

The only way for us to create any facet of a utopian world is through creation and manifestations of love. We must face our inner darknesses individually before coming together as a collective to create and build from a place of love. Any other trajectory fueled by fear or hatred will continue the cycle of pain and suffering we are trapped in currently.

Thanks for the thought provoking article, Alex! Hope you and the family have a lovely Christmas and New Years!