Addiction Is Between You and the World

Reciprocal narrowing and opening

We all know opiates are highly addicting, and it probably comes as no surprise that they are the drug of choice in times of political upheaval and trauma. During the Vietnam War, for instance, about half of the soldiers experimented with narcotic drugs. It’s estimated that 34% regularly did heroin, many of whom experienced symptoms of opiate dependence.

Yet there’s another story about Vietnam vets and drugs that’s less often told. How upon returning home, only 10% of these veterans ever tried heroin again. Or, even more surprisingly, of those who did tempt to tickle the beast, only 1% became re-addicted! While this says nothing about the rampant PTSD and addiction among vets—and how we have utterly failed to provide adequate mental health support for our veterans—it does suggest something interesting about addiction.

What if I were to tell you that addiction does not just live inside you, but rather that it exists between you and the world?

In a brutal fucking war, in a foreign jungle, in perhaps the most inhospitable conditions imaginable with the average life expectancy sometimes in the minutes, you might want to get high and escape that situation. If you’ve ever seen the movie Platoon—especially the scene with Charlie Sheen, Willem Dafoe, and the squad getting lit—you understand that these soldiers needed distraction from the atrocities they were forced to commit and face. They needed relief.

Once back in America, many of these vets were surrounded by a new social setting with friends, family, fireworks, and whatever else we might imagine in this quaint suburban time on the verge of being displaced by postmodernity. Vets were thrown into an utterly new environment that—while it may not have involved the trenches—still threatened to disrupt the fight-or-flight machinery of their bodies. Nonetheless, it was enough for many of them to never touch black tar heroin again.

Johann Hari has, at least in part, made a bestselling career out of claiming that addiction is rooted in a deep search for meaning and connection.1 If there’s one thing in common across all process-oriented recovery programs from the 12 Steps to Buddhist based to more modern versions—it’s community. Those prone to addiction are sensitive beings who often feel an acute sense of outsider-ness and alienation from the culture. Recovery requires truth, love, and a warm welcome that tells a newcomer’s nervous system: you’re right where you need to be.

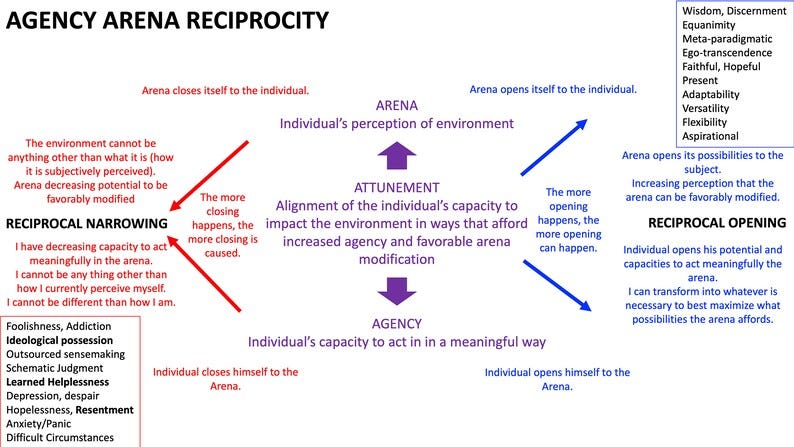

This does not mean that addiction is simply a social problem rooted in a need for belonging. Addiction is ultimately far more nebulous than this, more like an ambiguous monster that pervades all aspects of modern living, woven into the fabric of our consumerist lives. It’s anything but simple. As neuroscientists like Marc Lewis point out, addiction is a type of reciprocal narrowing. In cognitive science, reciprocal narrowing refers to how the brain adapts to new experiences and environments. When we are immersed in addiction, we experience a cognitive narrowing of our ability to see across multiple perspectives. We become singularly focused on the thing, or ‘object,’ we are after. As a result, we become increasingly dependent on securing this singular object in order to experience joy.

Consider this cycle in the context of drug addiction. First you take a drug, for instance, that awakens the pleasure centers of your brain. Afterward, your brain desires a repetition of the same reward again and again through cognitive reinforcement. In the process, the synapses of your brain begin to form a dense inner network of neurons that suddenly becomes extremely difficult for the mind to circumvent. As the brain becomes more desperate to seek out the same reward cycle in endless repetition, your perspective narrows progressively with it, and you begin to lose agency over your life. The people, places, and things that might normally give you pleasure suddenly begin to appear lackluster. The world around you shrinks: there is just you and the high you need to function. Possibilities for other courses of action outside of the reward center you depend on diminish, whittling your psyche down to the viciously reinforcing cycle of reciprocal narrowing.

It's worth mentioning that the majority of people who suffer from severe addiction begin their journeys from a place of deprivation and restriction. In fact, it explains a lot of why people in inner cities and the Rust Belt and other communities on the brink feel marginalized and riddled with desperation. Gabor Maté alludes to this idea in Myth of Normal by explaining our need to capitalize on an unequal distribution of resources to secure a liquid economy. Given this, it is no surprise that communities who have been narrowed or disenfranchised by this economy are more likely to become addicted to alcohol, meth, Oxy—or motherfucking TikTok—because such drugs further narrow their neural pathways within an environment that already feels unbearably limited.

All this begs the question, is addiction a brain disease or the result of a toxic culture? As I’ve written about previously, through understanding the science of addiction, I began to realize that my addictive transgressions, crimes, and ways I hurt people were less the result of some inherent moral failing and more that of a human whose dopamine receptors had become too unilateral, too ruthlessly confined. I believe the disease model is a useful concept at a useful time in recovery—that is, early on. Then, as I further developed and studied psychology, I began to see the disease model of addiction as a suffocatingly narrow reality that only accounted for biology. This perspective shift allowed me to feel even more compassion for myself and others whose focus had become as myopic as a pinprick of light in a dark room.

In this way, I began to reframe addiction as something that wasn’t a disease so much as a dynamic relationship between an individual and the world he is looking to feel at home within. We need to feel like we can play this game of life meaningfully in the arena we are born into. We play on a stage that, as actors, we only have so much ability to change. Yet the latest research also suggests that recovery requires a healthy degree of motivation from the individual, which, as obvious as it might sound, reinforces the notion of addiction as something malleable—between the relationship a human chooses to build with his environment rather than fall victim to its perceived limitations.

You might be thinking … all of this sounds great, but how do I flip my own coin? What happens when I turn reciprocal narrowing on its head, what will I find?

Reciprocal opening, which can be understood as a kind of progressive expansion of the things that bring you pleasure. Professor John Vervaeke offers one solution in the form of psychotechnology, a fancy word for engaging in a practice that allows you to see new possibilities for your life. This includes meditation, dynamic group processing, psychedelic interventions, and psychospiritual practices like yoga and Tai Chi. It can also include the reciprocal opening found in subtle ways, through finding little rituals and routines that help you reset, such as brewing a glass of tea, doing a few rounds of boxed breathing, or looking out the window and noticing the sunshine.

Reciprocal opening can be described as the move towards enlightenment, or a move towards embracing suffering as part of the human experience rather than contrary to it. Take, for example, the Buddha’s insight that suffering is core to the human condition. If we consider this true, then maybe reciprocal opening is something like finding new pathways where there were only obstacles before.

Said another way, reciprocal opening is interdependent with love. When we fall in love, we suddenly become open to new possibilities for our future. Our lives suddenly feel more meaningful, our sense of belonging more relevant. When we fall in love, we see a way to simply be again. To exist in the world without black-and-white conditions for happiness. Instead, there is only unconditional joy in the chance to get lost doing the things we love. Or, maybe, chasing the person we love, the one who will help progressively open our minds and hearts to the world.

Further proof addiction is a complex monster: In Hari’s widely watched Ted Talk on the subject, he cites the infamous Rat Park experiment, where isolated rats who were addicted to cocaine stopped using once they were placed in a super dope rat theme park with other rats. This was meant to imply that addiction is the result of a lack of connection. Alas, this is a piece of research that, unfortunately, not only has never been replicated but has also since been debunked. Hari’s critics claim he cherry-picks research and ignores the brain science of addiction in place of a simplistic, more exciting cultural narrative.

Excellent insight into addiction. I'll have to read it again because it often takes me longer than others to process complex information. I'm currently reading two of C. Jung’s essays on analytical psychology and must read each page twice, sometimes thrice. Worth it.

I recently hit five years clean and can relate to everything you said. I'm a new subscriber and look forward to rifling through the archive and forthcoming posts. I love your work.

I just started my newsletter here, and it’s been a rocky start, mostly incomplete thoughts. You might enjoy my first post. It’s about my early sobriety and discovering misconceptions of selfhood.

Check it—or don't. My feelings won't be hurt.

https://open.substack.com/pub/coreyswords/p/the-act?utm_source=direct&r=1s99nq&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Love the systems thinking / parasitic view. Very useful. Changing plans for 2023 holidays now. Heading to super dope rat theme park instead. Thanks Alex!